A Building review in Architecture Today November 2017

I am standing on a terrace 7 floors above the new King’s

Cross re-development, and everything is pink, a deep, intensely saturated rich,

reddish pink. The concrete paving on which I am standing is pink, the

balustrades and handrail are pink, as are the four storeys of façade rising up

above me, even the glass reflects the meaty hues of the building’s fins and is

a shiny metallic version of the same pink.

The effect is hallucinatory, thrilling, and set against the

greys and blues of the London sky, intensely picturesque and painterly. The

building is empty, having been externally completed, with internal fit-out only

just beginning, and so the total envelopment in colour that I am experiencing

is a momentary state. Set to become Neu-Look’s headquarters, this terrace will

be filled with furniture, and be busy with variegated employees, as will the

two equally pigmented outdoor loggias on every floor. Rather than the building

attempting to provide a “neutral backdrop” as most tend to, here all the various

activities will be situated within, and contrasted against, a refreshingly

confident and virtuoso act of aesthetic place-making through colour, that will

easily accommodate the richness and variety of daily life, whilst maintaining a

powerful and distinct sense of singularity.

R7 at Argent’s King’s Cross was the first large commercial

commission for Duggan Morris Architects (now splitting into xxxx & xxxx),

which makes it all the more astonishing for what a virtuoso, inventive, and yet

highly poised piece of urban and architectural design it is. The building was

designed as a speculative development, and yet the architects managed to work

with the client to come up with a scheme that takes a lot of risks, aesthetic

and programmatic, all of which seem to have paid off handsomely, with the

building now almost fully let.

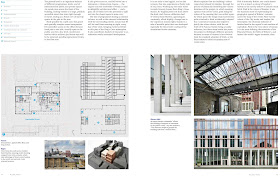

The ground level is an ingenious balance of different

programs, levels, and of interconnected public and private spaces. An arcade

runs across the front of the building, leading visitors to a large, publicly

accessible street that runs right through the heart of the building, ending at

a future row of start-up spaces in the plot to the rear. Made possible by a

split core, this rather grand and spatially complex room, pink concrete floor

included, incorporates fob-controlled access to the office elevator bank just

to one side, visually open to the public save for a low level, unobtrusive

barrier (Morris says there are plans to remove this pending operational review

in the first year), as well as access, and full views into a restaurant, a

three-screen cinema -the angled concrete underside of which is used to

delightful architectural effect- and a gym, all of which have the potential to

spill out into the shared space in some way.

The mix of programs sharing a common volume, as well as the

nuanced relationship with the surrounding streets, means that R7 will be used

throughout the course of each day, morning, and night, and throughout the full

7days of the week, contributing greatly towards bringing varied activities to

this part of the King’s Cross masterplan. It also contributes buckets of

character to an otherwise overly restrained development. It is not only in the

loggias, and on the terraces, that one experiences a fleshy rush of racy hues.

Walking up the main street towards Granary Square from King’s Cross, R7 happily

peeks out from above the drab, dark brown utilitarian shed of St Martins,

appearing to constantly, albeit slightly, change hue in the capricious London

light, thanks to a special mix of metallic paint that was developed especially

for the powder coating of the aluminium façade elements in the project.

Morris explains that the building’s colour came almost by

mistake, through the process of physically modelling the various iterations of

the project, in which massing options were colour coded, pink being the colour

of the massing that was settled upon, by which point the design team had become

quite attached to their accidentally adopted hue. There were also contextual

reasons that helped justify the colour choice, with the red of St Pancras being

a handy reference, but these seem beside the point, the project is thrillingly

different precisely because its sense of context is less obvious than the

standard adoption of brick, or the faux-industrial (albeit exquisite) reds of

cor-ten.

Pink is intensely British, one could almost say it is as

much a colour of London’s history as the murky yellow of London stock brick.

Pink is the colour of Empire, it was the standard mode of representing the

geographic spread of Britain’s colonies across the map of the world. Pink was

the colour of the City trader and banker, his breastplate, the chummy indicator

of insider-hood in the capital’s vast machine of capitalism. Pink is the very

colour of money, it makes up the most defining characteristic of the Financial

Times, the bible of Britain, and indeed the world’s upper economic class.

Over recent decades pink has also come to embody other

qualities and groups, from the development of a strange, and problematic link

between the gender identification of young girls and the colour, to the

adoption of the hue by the LGBT community, to its recent emergence as the

colour that defines a generation, with a particularly light tone of it being

called “Millennial Pink,” and showing up in everything from graphic design to

fashion, to music videos, product design, architectural student visualisations,

and now, perhaps unintentionally, a very large building in King’s Cross.

Apart from being tempered by set-backs, the building’s mass

is further broken up by being divided into two blocks, each coloured in a

different shade of pink, one light, like white skin, like the Financial Times

or Millennial Pink, and the other a deep, almost red pink, like the warm colour

of the flesh under the skin, or inside the body, closer to the hyper-saturation

of the pink used in supermarket princess dresses. It is these associations, and

more, that are projected over King’s Cross by this intriguing newcomer.

There is a long history of Modernist architecture that

exults in the sensual and associative effects of colour, a history that has

seen far too few recent offspring. There has also recently been a preponderance

of architects in the UK who are only able to generate facades directly justified

by their immediate material context, rather than attempting new aesthetic experiments,

or orchestrating their tectonics through the referencing of broader cultural

contexts. Duggan Morris’ R7 building brilliantly, subtly, and with style

manages to leave where the late Modernists left off, as well as -even if

accidentally- bringing an incredibly rich world of references and association

to life in a building that itself, through its clever layout, will bring much

actual -as well as aesthetic- life to its lucky context.

No comments:

Post a Comment